I try not to think of my childhood. Much in the way you shun shameful conversations from that one party, I efface my entire early life. It’s not that some terrible abuse occurred, or that things have been repressed; in fact, I had a very okay upbringing. It wasn’t that bad. Back then I was obsessed with objects, toys—they couldn’t leave me. I suffer from a disease common to the lonely: crippling logorrhea. I was, am, a talker. These poor toys were forced by virtue of their lifelessness to listen to my nine-to-twelve hours per diem of nonsense. I brought Archer, Vegeta, and Teddy on every road trip and paid them more mind than just about anybody.

For my memory, life started at twenty-one. When my dad starts a question with, “Remember when you all …” I shut down and tell him no, no matter what it is, but not because of the pain in those old times. Rather, I hurt so much now that fondly remembering a time when I didn’t is too wishful, too contrary to how things turned out, and thus it is excruciating. When strips of you are falling into the spit, thoughts of water are unbearable.

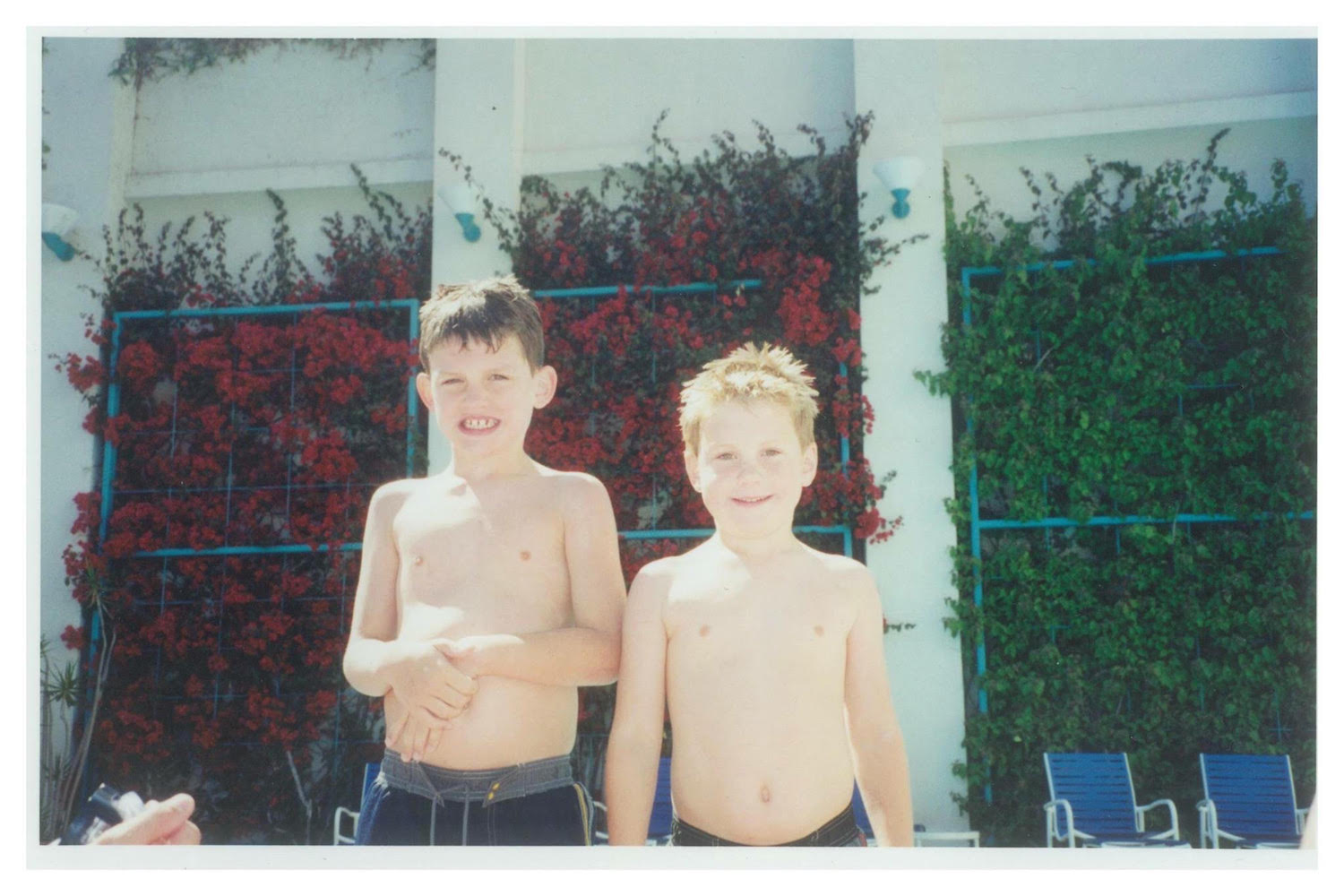

My brother’s birthday was last Wednesday. He would have been twenty-four. On a lot of those road trips, I ignored him for figurines, though we did have our own little language. It only worked one way. My diffident little brother, our only blonde, would whisper his wishes to me and only me (“I’m hungry!”), and I would relay them to mom or dad, annoyed by my own honesty. He trusted me with this vital dispatch because I was his big brother. He childishly thought I was capable of protecting him, of vouching for him. But I never really wanted to provide support, so caught up was I in my toys and the stories I told them.

I haven’t really spoken since his car collided with another car, head on, at an intersection three miles from my home. Mine then became a sort of quarter life: most of my energy is now spent keeping certain feelings distant. From what I remember of the morgue dialogue, many of his long bones were instantly crushed. I think that’s how it happened. But he was too still and parallel behind the glass on that cold slab. I’m not sure whether he was even a “he” anymore, by then. I remember blood on the tips of his lips, not dripping, dried. His eyes were sleeplessly closed. His jaw had been broken. They said he died instantly, no pain. My own would take another year. True grief crawls.

A few days later, I spoke to his body at the creepy funeral home. It was lit synthetically, and the profusion of fora was oppressive. You always get the sense at these places, despite how nice the employees seem, that they are desperately waiting for you to leave. But even with me squeezing his pale arm and all my quiet, choked supplication, he did not respond. He did not so much as flutter an eyelash. He was dead. The days following his wreck were met with hysterics from all involved, but my own tongue felt like an anvil. I vividly recall that I tried to say, over and over, over my torrential tears, over the unmoving object that was now his body, “We were supposed to grow old together.” I don’t really have any childhood memories without him.

What’s so hideously fascinating about it is that, when he was broken physically, I broke in all other conceivable places. In my head, I suffered not a snap so much as a gradual weakening of elasticity. My emotions broke too: I would feel nothing but emphatic fear for many years after his passing. Drugs were always too disorderly for me, so to sleep even a wink, I had to regiment and endure arduous daily exercise—my natural trauma tranquilizer. This has, in turn, engendered many irritating injuries all over my body. So I suppose, in a strained-metaphor sort of way, I broke physically, too. Or maybe I am currently breaking.

Some things I guess you just don’t get over. Time doesn’t do a damn thing except tick, and it certainly didn’t heal me; I just became better equipped to bury and hide. And what’s worse is I miss him more today than I ever have, though mostly I regret his missed future for him. Admittedly, this feeling, this yen for his presence, is a nice break from the well-worn routines of morbid obsession, swirling paradox, am-I-weird reflexivity, panicked hyper-vigilance, violent intrusive thought, and why-am-I-such-an-irreparably-bad-and-sad-person type of conundra that drench me nightly, still.

See, typically I would try to drown all this mental imbroglio and self-pitying sobby shit in irony or irreverent metaphor, but I figured, Fuck it. I’m too tired tonight. For one day a year, for him, maybe I can be real and upfront about my emotional state of affairs. To be terse, they’re “not good.” I never healed or moved on from. This whole piece is surely riddled with lazy cliches, so why not another: there hasn’t been a single day since it happened in which I have not thought about my brother. Not one night sans suicidal terror—a sort of selfish, fatal desire to join him somewhere in a cloud.

In fact, that’s where I’m heading now: I’m in yet another bed, in the penumbra of night, alone in and confused about the fact that everyone I know is always silent, including me as I shake and sweat with sorrow. If I had a backbone or a belly not so yellow, I’d have taken too many pills and ended this silly farce a while back.

And I wonder if I’ll ever be able to think of childhood again. He circumscribes those scenes now—a phantom of every guilt I still bear. When I started this, I set out to write about his life, a sort of posthumous birthday gift for him. But the whole thing ended up being about me: my needs, my story, my corrigenda. Solipsism is as selfish as grief—each shrinks all life into objects of our own thinking. Yet I believe there’s a way to obviate this: it’s sincerity, transparency, connection, those things I could never offer my little brother. So, if I can’t think, I’ll speak.

I’ll write. Not to toys or bodies, but to people. I’ll go beyond belated relay—I’ll share. No matter how cowardly I feel, I’ll let it loudly hurt. I can do this through him because he taught me; he’s my big brother now.

Sometimes, I find the courage to dream of him. He’s usually just in the abstractive background, in parade stance, waiting for me as I try not to notice him. Other times we’re grown men, older. We walk this white roadblock together, and he places his pale hand on my shoulder. He always looks me in the eye, needlessly apologizes, and then says goodbye. All of this in our little language.

My now sad childhood was retroactively shattered at an intersection on US 60, January 14, 2015. These written thoughts and a couple of photos are all I have of our life. Death always ripples out and rapaciously takes more than one with it, you know. I shouldn’t be so scared—I am just one of those ripples. But it’s gotten so late. Let’s just dream and sing, okay? Just tell me what you want me to tell Mom. I’ll tell her, I promise. Is it french fries again? You’ll need to speak up. Okay, I’m coming back there. Hold on.

Wow!